One of the main lessons of recent financial diaries research is that low income often means erratic income. If you live on $2 a day, you don’t get two bucks each morning—you might make money at the beginning of the month and then not see another paycheck until weeks later. Unskilled, informal sector jobs come and go, and health problems add to uncertainties. As a result, one of the key financial challenges of poor households is to budget volatile income over long stretches of time.

That theme has also been popping up quite a bit in FAI’s nascent exploration of the financial lives of low-income U.S. households. Partly that’s because the Great Recession set off a wave of think tank research about income volatility. Last summer the Rockefeller Foundation launched an “economic security index” to track the number of households experiencing a major loss of income (defined as 25% of more) over the course of a year. The Urban Institute has been publishing an entire series of reports as a part of its “Risk and Low-Income Working Families” research initiative.

But the conversation stretches back much further. Starting in the mid-1990s, academic economists Peter Gottschalk and Robert Moffitt began publishing papers showing an increase in income instability for working men starting in the 1970s. Other researchers bolstered those findings, and the conversation reached something of a fever pitch in the mid-2000s with the publication of "The Great Risk Shift" by Yale political scientist Jacob Hacker. Research by the Congressional Budget Office disputes that income instability has risen all that much, but as Justin Wolfers once astutely pointed out, if families face too much risk, that’s the problem—not whether or not the amount of risk has recently budged in one direction or the other.

What does income instability mean for low-income households in particular? There’s not a whole lot in the literature that breaks down instability by income band. That’s largely because of how tricky it is to nail down categories. If income is, by definition, volatile, then at what point do you decide whether or not a family is low-income?

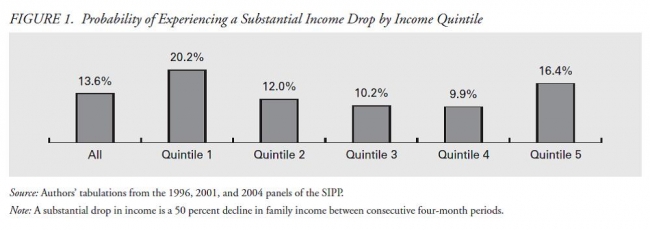

One notable exception is a 2009 paper by Urban Institute economists Gregory Acs, Pamela Loprest, and Austin Nichols. Using data from the U.S. Census’s Survey of Income and Program Participation—the go-to- source for income volatility research—the authors simply define households by their incomes at the start of the observation period. That’s by no means ideal, but it does give an easily digestible result:

What’s immediately apparent is that households at both ends of the income distribution are much more likely to see a substantial drop in income —defined as a 50% decline in family income between consecutive four-month periods. (For this study, the authors only looked at families with children and a head of household between the ages of 25 and 61, which should for the most part tease out the effect of people retiring.) Notably, a full 20% of the poorest fifth of families lost at least half their in income at some point during the course of a year.

At first pass, that feels pretty grim. There are a plenty of reasons why family income might drop, and many of them aren’t necessarily signs of distress—perhaps a mother has quit part-time work to stay at home with her new baby. Nonetheless, it’s hard to imagine that most low-income families don’t experience great hardship when half of their income is suddenly missing.

Yet the study also reveals that low-income families are incredibly resilient. Indeed, within a year, more than half of families in the lowest quintile are back to their original level of income, a far greater share than in any other slice of the income spectrum:

That is to say, low-income families are more likely to see a massive downward swing in income, but they are also less likely to experience a sustained drop. One might therefore argue that such families could make good use of financial tools to smooth income over time.

In fact, there is evidence—not to mention common sense—that families do just that. A series of papers by economists Karen Dynan, Douglas Elmendorf, and Daniel Sichel suggests that over the past few decades, as families have acquired greater access to credit, household spending has become less responsive to changes in income. Credit cards, home equity loans, and other forms of consumer borrowing have gotten a bad reputation in recent years, but, used prudently, they do have a way of helping families out.

And here we arrive squarely back in FAI’s comfort zone. Not surprisingly, one of our big questions is whether or not low-income households in the U.S. have access to the right tools to smooth consumption. Are high-interest-rate credit cards and payday loans helpful mechanisms for families experiencing a loss of income, or do they simply make things worse? We continue to explore.

Barbara Kiviat is a David Bohnett Fellow at New York University's Wagner Graduate School of Public Service.