The microcredit movement is premised on the idea that access to capital will be liberating, empowering, and profit-making. But as the Indian microfinance sector closed out another year, it’s hard to be so ebullient.

The Indian microfinance crisis continued through 2011, and we now have good data and the distance to get a clearer perspective. More than anything else, the data show disturbingly high levels of debt pushed into communities. While the government blames microfinance institutions for excessive lending, government-sponsored self-help groups turn out to have contributed to a large share of the problems.

Too much debt

Whether or not there has been excessive lending and who is responsible for it is assessed in the M-CRIL Microfinance Review 2011. The state-wise picture is disquieting. Andhra Pradesh (AP) has, by far, the highest coverage of 411% – for every excluded family (eligible for microcredit) more than four microfinance loans outstanding at end-March 2011. All the other main southern states –Tamil Nadu (290%), Kerala (265%) and Karnataka (144%) – also have high coverage ratios along with Orissa (123%) and West Bengal (106%). Since distribution across districts and across families is well known not to be even, it is apparent that there is significant multiple lending in all of these states – see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Coverage of eligible population by microfinance loans (MFIs + SHGs)

The government’s role in Andhra Pradesh

What is interesting is that while the number of MFI loans in AP is just over 100% of the number of eligible financially excluded families, loans from government-sponsored SHGs are actually 310% of that number.

More importantly, to the extent that microfinance loans are not evenly distributed this means that there were a significant number of financially excluded families in AP that had as many as 7-8 loans at one time and a number of these were SHG loans. This raises the question whether it is the government’s SHG programme rather than MFI lending that is responsible for multiple lending and the crisis. It seems that government welfare over-reach cannot escape the blame for the crisis even if the MFIs did as much as they possibly could to have “the sky fall on their heads.”

The analysis reveals that even if debt were distributed equally amongst all eligible families in AP there would be over-indebtedness to the extent of 9% of the average income for such families – assuming that 40% is the maximum reasonable debt servicing capacity at the average level of income (around $2,000 in AP) for financially excluded families. At lower assumed levels of debt servicing capacity, the level of over-indebtedness is higher. (The M-CRIL Review incorporates a new approach to the assessment of aggregate over-indebtedness in a region.)

Warning signs in other states

Paradoxically, there are also indications of over-indebtedness in the less well served states of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh – three of the largest states in the country on the basis of population. Each of these states has much lower per capita incomes and, therefore, lower proportions of family income available for debt servicing. The reason this has not led to a crisis in those states is that the microfinance penetration there was just 16-21% by end-March 2011 and it is likely that the outreach of both SHGs and MFIs is mainly to the upper strata of eligible families. Further expansion of microfinance in these states could cause more serious repayment problems than the few incidents that have come to light so far, unless the average debt is lowered.

Political risk and the drying up of commercial funds

However, the effects of the crisis resulting from the AP law spread much more widely than the state of Andhra Pradesh. This effect was not due to any delinquency contagion reaching clients outside the state but rather due to the drying up of commercial bank on-lending funds to MFIs. Thus, the manifestation of political risk that they saw in the form of the AP law resulted in banks reducing their lending in the last quarter of the financial year (April 2010 to March 2011) to a minimal level. This affected MFIs all over the country (irrespective of where they operate) and is the primary reason for the low (25%) growth in net portfolio of the leading MFIs during the year. Since there is a limit to the equity it is possible to raise (and it takes longer to mobilise), while deposits are not an option, MFIs were forced to limit the growth in their portfolios.

Shrinking portfolios

MFIs have actually had to shrink their portfolios due to the reduction in funds available for microfinance from risk-averse commercial banks. Since total funds deployed in microfinance have increased by just 5.6%, the 25% growth in portfolio during the year had to be achieved by liquidating short term investments, reducing dramatically from the 21% level of March 2010 to just 0.02% of assets in March 2011 – such is the dependence of Indian microfinance on commercial bank funding.

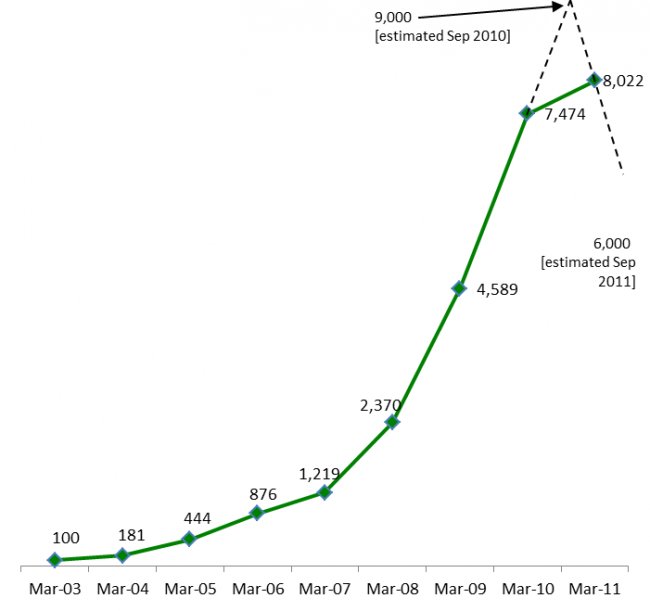

Figure 2 presents CRILEX – M-CRIL’s index of microfinance growth in India – for end-March 2011 and, since accurate information is not available, an estimate for 30 September 2011.

Figure 2

A year earlier, by 31 March 2010, CRILEX had reached the level of 7,474 (with March 2003=100), up from 4,589 in the previous year registering a composite growth of 63% in the year April 2009 to March 2010 and continuing the trend of the previous years. However, during the year to March 2011 there was a slowdown to just 7.3% in composite growth and the index reached 8,022. More significantly, the annual growth figure masks the dramatic developments during the year; until early October 2010 MFIs continued to grow at a blistering pace with the index estimated by M-CRIL to have reached 9,000 from the 7,474 of end March 2010. However, during the year since the onset of the great crisis in Indian microfinance, there has been a considerable decline with CRILEX estimated to have fallen to 6,000 by end-September 2011 representing a decline from the peak of 33% in the outreach of Indian MFIs. By end-December 2011, M-CRIL estimates this will have fallen even further to around 4,500 or perhaps 50% of its peak level.

The moneylenders rise again

If there was a crisis of over-indebtedness to MFIs earlier, there is a fast developing rise of moneylender loans now. While some low income families have had welcome relief from MFI payments, many more have been thrown back into the welcoming arms of moneylenders. It is unlikely that this outcome will lead to the maximisation of welfare in Indian society. The year in review has been a dismal one for financial access and the welfare of low income families in India.