No consumer likes overdraft fees. Overdraft fees are often unexpected, expensive, and in some cases undeserved. What’s more, they can wreak financial havoc on households living on a low-income.

But the larger issue is not the fees themselves. It’s the lack of transparency surrounding them and the widespread consumer distrust that results.

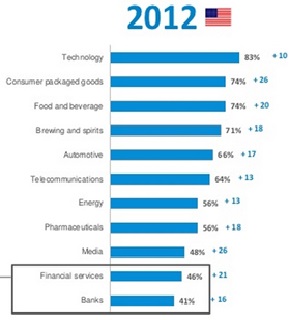

Edelman is a PR firm that surveys people around the world to create an annual Trust Barometer (among other things), which gauges levels of trust in different institutions. In 2012 it found that only 41% of respondents in the U.S. trust banks – which, by the way, were at the bottom of the list right along with financial services. The year’s ratings on banks are second-worst only to 2011, when they hit a low of 25%.

Consumer distrust is a problem in its own right. It can lead to feelings of stress and betrayal, especially among those who end up with questionable fees on their bank account statements. Furthermore, distrust is linked to real financial hardship, as shown in this 2012 study where the authors find that those who are less trusting tend to have less money saved, more debt, more missed payments, and lower net worth.

Banks are not responsible for the financial health of their customers. But they do have an obligation to not actively harm them. To the extent that banks feed into consumer distrust by acting with little to no transparency regarding overdraft fees, they areharming customers, actively.

The link between trustworthy financial services and consumer well-being has been flagged by entities seeking to eliminate harmful practices. Some offer tools and certifications encouraging providers to internally adopt a principles-based approach to consumer respect. Examples include CFSI’s Compass Principles that target institutions in the U.S., Treating Customers Fairly in the U.K. and Australia, and Smart Campaign within the microfinance industry. While I think these are essential, I’m not convinced that a certificate will be quite enough to raise the banking bar. On the other hand, regulations from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau stand as top-down rules to curb problematic bank behavior. But this rules-based approach can “degenerate into a ‘whack-a-mole’ game: as soon as one bad behavior is prohibited, another one pops up.”

Ideally financial service providers would have a profit incentive to raise the bar on their own. Edelman’s 2012 report found that consumers would most increase their trust in banks that “have ethical business practices”. Banks with “transparent and open business practices” also ranked highly. Consumers, especially those who are low-income, know when their bank comes up short in these areas – particularly when it affects their account balance. In theory, banks with these qualities would attract more loyal patrons and thus more income streams.

As evidenced in Lisa Servon’s recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, finding profitability in low-income consumers remains the great puzzle in our field. Non-profit and cooperative business models have and will continue to play an important role in serving these customers. But the for-profits likely could be doing much better. Banks must begin to hold up transparency and earned trust as desirable in their own right.

This post was written by Julie Siwicki of the Financial Access Initiative. The views expressed therein are those of the author, and not necessarily of the USFD project or its funders.