The Normal-Ish Edition

Editor's Note: I recently learned that my paper with Michael Clemens (that one I referred to last week that took 5 years from submission to publication) on rethinking migration from the perspective of household finance is among the top 10% of downloads at Development Policy Review so if you're eager to read something non-pandemic check it out. Apparently at least a few other people have done so. And the paper on what is happening with microcredit in Pakistan is now officially published.

–Tim Ogden

1. Microfinance:

First I have to apologize to Hans Dieter Seibel for misspelling his name in the last faiV. He also pointed out that I haven't been careful in my use of the terms microfinance and microcredit in recent weeks. That's true. The reason isn't just carelessness however. While it's true that the immediate impact of the pandemic primarily falls on microcredit providers and less so on institutions that provide more than, or something other than credit, the ultimate impact on microfinance from the failure of microcredit is so devastating as to not matter so much. The fact is that the business model of microfinance is dependent on the income from credit operations. There is a reason that the modern microfinance movement began with credit: there's a business model there that can function at scale. We're still not there with microsavings, and even farther away with microinsurance. If you lose the ability to cross-subsidize savings or other financial services for the poor from cash flow on credit, those services are largely going to go away. Yes, of course, there are some microfinance institutions that have large scale microsavings and those are almost certainly better off in the current crisis—but the reason they were able to reach scale was because they recruited and paid for a customer base and staff with the income from credit operations.

There's another way that microcredit isn't used carefully and at times conflated with small dollar credit. I make the distinction, à la Yunus, that microcredit has a specific pro-poor motivation, while small dollar credit does not (it may or may not be pro-poor, it just doesn't have intentions or pretensions to be so). Here's an example from the New York Times which frames a story about predatory small dollar lending in Jordan as somehow related to the microcredit movement.

So I should be more careful in making the distinction between microfinance and microcredit, and not assume that the underlying logic of why a crisis for credit is also a crisis for financial services for the poor in general (payments aside) is obvious. But I think the bottom line is the same: this is an existential crisis for microfinance, not just for microcredit.

On the topic of microfinance, used correctly, here's a new paper from Shilpa Aggarwal, Valentina Brailovskaya and Jon Robinson on a savings intervention in Malawi that provides people with multiple lockboxes or mobile money accounts to save in. The paper is remarkable for several reasons. First, it finds that there is meaningful savings in the treatment group ($27/month average). Second, that additional lockboxes increase savings by about 40%. Third, the take-up and usage of the lockboxes is quite high. But the best part is that it has one of my favorite paragraphs in the microsavings literature (the last one in the introduction), which takes seriously the limitations of most of the savings experiment literature: people don't take up the accounts or use them very much in most interventions.

2. Supply Chains (and SMEs):

Beth Rhyne, our new visiting fellow at FAI, has a piece up at Next Billion on the current crisis, in essence asking the question: what kind of crisis is this? Some crises, like natural disasters, destroy physical assets; some, like the Great Recession, destroy financial ones. But the pandemic is different—and therefore we need to think carefully about what recovery and assistance look like. Beth notes that in her experience after a flood in Mozambique, people were able to recover quickly despite losing their physical assets because they didn't lose their human capital—and specifically their networks of family, suppliers and customers and the like. But what do we know about the pandemic and its effects on such things as supply chains? Not much yet—but it's something we should be paying a lot of attention to. It's possible that the pandemic won't affect relationships and supply chains. It's possible that it will matter a great deal: from urban displacement, to mortality, to insolvency.

Here's an example: Felix Salmon writes in his Axios newsletter about small farm agricultural supply chains around big cities in the United States permanently breaking down. Small farms in these regions have formed a symbiotic relationship with restaurants who would "buy local" and process the crops themselves, marketing "farm-to-table" and charging accordingly. Those restaurants are now closed or operating well below capacity. The farms simply aren't set up to sell into different supply chains. In a survey, Salmon reports, 90% of the farms say they will go out of business if restaurants are operating at 50% capacity this summer. So even if the restaurants survive financially, they will eventually close for lack of supply. The combination of the two sets of closures will cost a lot of jobs, with further effects on other businesses.

Here's Marc Bellemare and co-authors looking at Indian agricultural supply chains and their pandemic-caused disruption. The Indian agricultural sector is in the midst of a move from "traditional" to "transitional", with increasingly long and interconnected supply chains. Other key facts: 85% of the firms in the supply chain are SMEs in towns (not villages) and private enterprises handle 96% of the total supply chain. That's good for the development of the country, perhaps less so for resilience in the face of a major disruption.

That brings us to a little discussed trade-off for SMEs and economies when it comes to formalization. One of the big concerns about the impact of the pandemic on small businesses in the United States is not just they are going to die due to the economic effects of the pandemic—and the small business apocalypse is upon us—but that the formal nature of those businesses is going to make recovery harder. You see, most small business loans in the US are personally guaranteed. So when the businesses fail, the owners' credit is destroyed. An informal business can potentially be more resilient because there aren't "permanent records" to follow them around. That doesn't make informality, and the toll it takes on productivity and ultimately growth, a better option than formality but it is something to pay attention to as we learn more about "what kind of crisis is this?" Especially as you hear calls for increasing formalization as a part of a "solution" to helping MSMEs weather the pandemic.

3. Convergence/Divergence:

That's a good jumping off point for more convergence/divergence discussion: there is convergence in the impact on small and micro-businesses, but possibly divergence on the resilience of those businesses in surprising ways. There is also divergence in the impact the virus is having for reasons that are very unclear. Some of the places you might expect to be worst hit seem to be doing fine, and some places that you would expect to be doing OK are struggling. But there is convergence in terms of a huge jump in global poverty.

One aspect of that jump/convergence is the impact on migration which is a vital part of livelihoods the world over (hey, check out that paper I mentioned above). Not only is the pandemic shutting down or reversing migration corridors, it's also having a major impact on remittances from those who had already migrated. Here's a new report from the Hrishipara diaries that notes the plunge in remittances received. And similar anecdotes from the Kenya diaries follow-up with particular attention to the impact that has on women since labor migrants are often the male members of the family. But there is also some evidence of remittances growing in response to the crisis.

We're also starting to see more and more policy divergence. Some countries, like Nigeria, South Africa, Rwanda, Burkina Faso and South Sudan, are easing restrictions driven more by concern of the lockdown's direct effect on livelihoods. But cases are surging in some of those places, like Kano, Nigeria. Other countries, like Colombia, are extending lockdowns but also allowing some re-opening. And then there are places like Indonesia where cases are spiking but there don't appear to be policy changes either way. It's enough to make one believe a study that assumes these policies are essentially random.

We're also seeing divergence in the US between states, in part clearly because of differences in the course of the pandemic, and in part because of local politics. Of particular note is that the re-opening itself could have very divergent effects on different businesses, and in different locales. The story about agricultural supply chains above noted the impact on farms if restaurants operate at only half-capacity. But it doesn't note that any restaurants may not be able to survive if they operate at half capacity—and that isn't just a factor of policy but what people will be willing to do regardless of "re-opening." Margins in many small businesses are thin and require high utilization to make the economics work. I think our prior should be that many small businesses will not re-open or will fail if they do re-open because of that issue. On the other hand, that may be very different in developing countries where there seems to be significant excess capacity in small businesses due to demand constraints (see this paper by Morgan Hardy and Gisella Kagy, and this paper on the GiveDirectly basic income trial). It's a question I'm really hoping to answer in our on-hold but still coming Small Firm Diaries work.

4. US Inequality:

It can be hard not to view everything through the lens of pandemic, but sometimes it's useful to turn the telescope around, so to speak, and view the pandemic through the lens of inequality. You are by now familiar with the very different impact the virus is having on Latinos and African-Americans in the US (and elsewhere).

Beyond that, there are the standard inequality issues with who will be able to cope and recover. To that point, the newest report from the JPMorgan Chase Institute highlights racial gaps in liquid assets. Liquid assets are a big part of being resilient to a crisis like this, when income suddenly drops. The racial gap in liquid assets is twice as large as the income gap, and gets larger in older cohorts (which I think I should interpret as a positive?). Likely as a consequence, Black and Hispanic families cut spending more during income shocks than white families. And that finding is showing up not just in JPMCI's data but in surveys of the effect on families in the US happening now.

5. Digital Finance:

Is this digital finance's time to shine? That's a question I think I'll be returning to over and over again. A few weeks ago, I attended a webinar put on by The Boma Project, the Busara Center and others on "the last mile" in digital finance in the context of the pandemic. You can see a recording here and the slides here. I was particularly taken by some slides presented by My Oral Village on the somewhat surprising nature of "isolated illiterates"—people who are on their own but illiterate and/or innumerate. In other words, these are people that are currently unreachable via digital finance, at least without a lot of (currently impossible) handholding. Now, I'm not arguing for the perfect being the enemy of the good. But I do think it's really important that we more explicitly recognize that unlike the microfinance movement (as discussed above) the vast majority of the digital finance sector is not firms with a pro-poor mandate or mission. So we just can't assume that digital transitions will expand inclusion rather than entrenching exclusion. Oh, and we should remember the risks to the people doing "high-touch digital" transactions.

But I wanted to take this opportunity to post a few links to things related to cash that I have had stashed since well before the pandemic, since it can be easy to overlook what we are losing when we make transitions under "emergency" circumstances. To start off with, we shouldn't, like Britain, be going cashless without a plan. And that plan should perhaps include, like Sweden apparently is planning, a mandate that financial institutions have to handle and process cash. Why is this important? Because cash is "vital public infrastructure" with truly unique characteristics that are especially valuable to the poor.

Graphic of the Week:

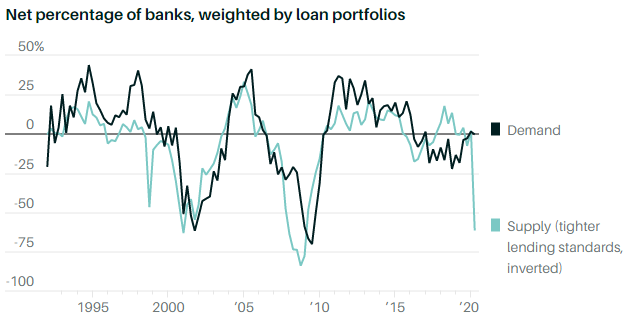

Above we discussed what kind of crisis this is; that influences but doesn't answer an important follow-up question: what will the recovery be like? The classic model of a lingering recession (at least from the business perspective is the interaction between limited consumer demand and limited supply of capital to invest and restart growth. For those hoping for a V-shaped recovery, the latest data from the Federal Reserve Board isn't encouraging: banks are tightening lending standards nearly as much as they did in the great recession (and keep in mind that small business lending never fully bounced back from 2008.). Source: The Federal Reserve Board, via Barrons.